ALR not the solution to the housing crisis

Agriculture faces increasing pressures from a variety of sources which could have adverse impacts on the sector as we know it, reduce food security and reduce the province’s revenues.

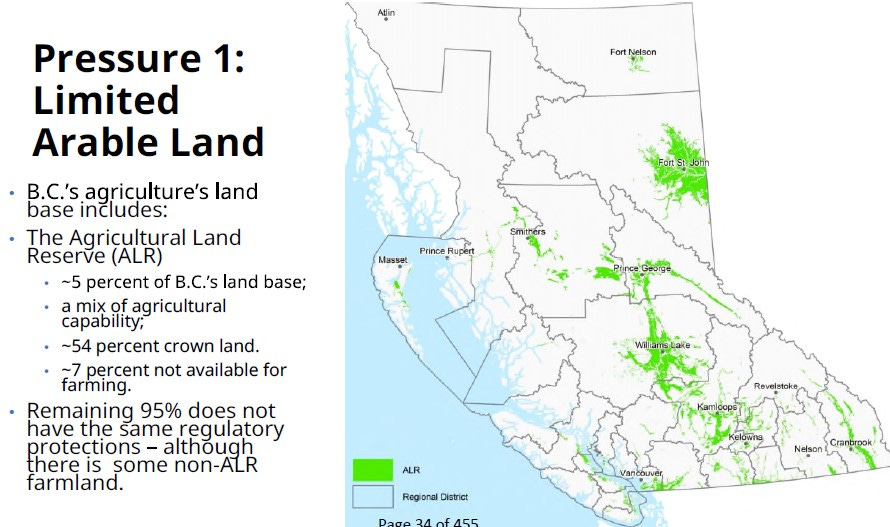

The second highest contributor to GDP in British Columbia, second only to mining, oil and gas, agriculture employs the highest number of people of any resource sector in the province. It does all that on barely five percent of the province’s land base.

For fifty years, the Agricultural Land Commission and the Agricultural Land Reserve have played a key role in protecting land for soil-based farming. A large portion of the lands protected in the ALR are located in the Peace River Regional District.

An important and growing sector of the BC economy, agriculture employed 30,000 people in 2020 – by comparison, forestry, logging and support services employed 18,000; mining and oil and gas extraction employed 29,000 people. In 2023, cash receipts from agriculture totalled $4.85 billion. Primary agriculture supports BC’s food and beverage processing sector, which had sales of $11 billion in 2020.

One of the pressures facing the agriculture industry is the housing crisis. According to Greg Bartle, Land Use Planner with the Ministry of Agriculture, who spoke to the PRRD board of directors at the May 30 board meeting, people tend to want to live near farmland in fertile valleys. This is poses a problem when developers and governments see farmland as potential room for housing, rather than food production.

“Agricultural land is critical to this sector, to the provincial economy and food security in BC,” said Bartle. “Once it’s paved over, it’s gone forever.”

Ninety-five percent of land in BC is located outside of the ALR, and of the five percent that is protected for agriculture, three percent is either treed or made up of lakes and rivers, Bartle said. “Only two percent is actually farming ready.”

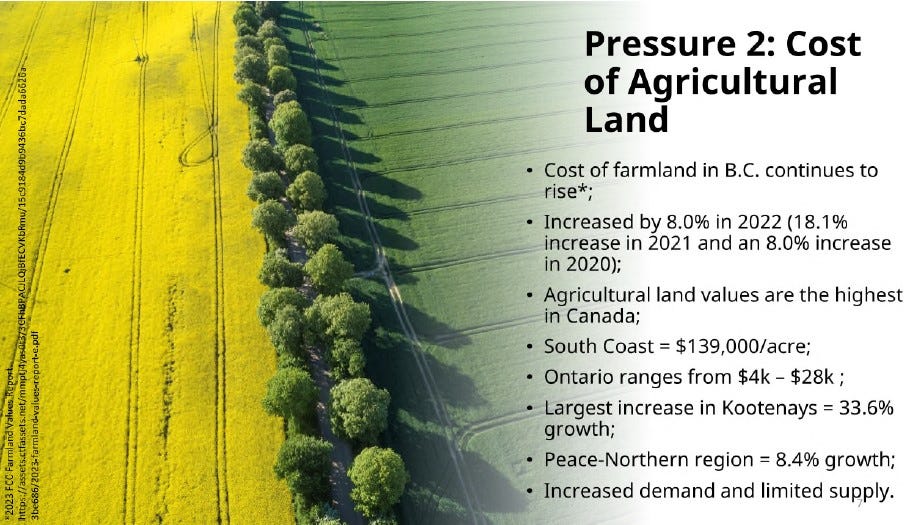

Non-farm uses are ever-encroaching, and increasing industrial and residential uses contribute to rising land values, which in turn challenge the economics of farming.

The pressures of urbanization continue to encroach on ALR protected lands, especially in the high-growth areas of the Lower Mainland, Okanagan and Vancouver Island, where 80 percent of the farm receipts are generated.

“Unaffordable housing is not just a Lower Mainland problem anymore,” Bartle said. “More and more people are looking at the ALR, and looking at it to solve the housing crisis.”

But, Bartle said, the ALR is not the solution to BC’s housing crisis, nor is it the solution to government planning on housing - it's called the Agricultural Land Reserve for a reason. Increasing residential development adjacent to farmland increases the number of complaints made against farmers, by people who don’t understand farming practices.

The ALR is also not the solution to the critical shortage of industrial land in locations such as Vancouver, where prices increased 17.5 percent in 2021 to $7.1 million/acre.

The cost of farmland, like industrial land has also increased in recent years, and British Columbia now has the highest agricultural land values in Canada. Prices for agricultural land increased 18.1 percent in 2021, and a further 8 percent in 2022. Northern pastureland values in 2022 increased 8.4 percent according to Farm Credit Canada’s 2023 Farmland Values Report.

“It’s pretty clear that there is an increased demand and limited supply,” Bartle said.

Bartle said that the recognition of reconciliation with First Nations is a central mandate of this BC government, including land and treaty negotiations.

“Much of the land under negotiation is included in the ALR, putting further pressure on this limited land base.”

Local governments can consider supporting agriculture with agricultural advisory committees, agriculture area plans, zoning bylaw updates, Offical Community Plan updates and education. Through their decision making, elected officials can make a difference, he added.

Agricultural land use inventories are a powerful tool, and local governments can utilize that data when creating plans, and to help raise awareness of agriculture within the community.

Another powerful tool is an Agriculture Advisory Committee, which the PRRD is looking at reinstating.

“In most scenarios, AAC’s are advisory, not involved in decision-making,” said Bartle. Made up primarily of members of the farming community, AACs are meant to provide advice to the board.

Area E director Dan Rose said that in Peace, it doesn’t feel like there’s a shortage of available land for industrial development, but he would like to see a proper inventory done.

“The inventory was done years ago, done very quickly and very poorly,” Rose said. “There’s lots of land available for development that’s not suitable for agriculture that’s in the reserve that needs to be removed. And perhaps other land added that should be in, that isn’t.”

Rose felt that an accurate inventory should be conducted before local governments like the PRRD start making decisions on what to do with the land.

The PRRD is not the only regional district to suggest this, and Bartle urged the board to continue to bring it up, perhaps at the Union of BC Municipalities.

“We bring it up at every UBCM. I think they get tired of hearing it,” Board Chair and Area C director Brad Sperling said.