BCVMC delays regulation implementation to consult northern producers

The British Columbia Vegetable Marketing Commission admits it made a mistake when it failed to consult with producers in the northern half of the province before extending its jurisdiction on January 1, 2024.

When BCVMC announced that it would expand its regulatory area to encompass all of British Columbia, not just the portion south of Quesnel, it received a lot of unsolicited feedback from vegetable producers. Before December 31, 2023, the BCVMC’s authority and regulations only applied to vegetables grown in BC below the 53rd parallel.

The Commission cited the impact of climate change on vegetable production opportunities, changes in agricultural practices that use controlled environment structures, as well the inappropriateness of regulating vegetable production in the southern part of the province but not the north simply because of “an arbitrary line” as reasons for expanding its regulatory area.

“Because of this feedback, we realized we could have done a really good job here of approaching the industry first and consulting with you guys before expanding the regulation,” Andre Solymosi, general manager of the BCVMC told the Peace River Regional District’s committee of the whole on May 30 in a presentation.

“We did not, and so we’ve decided to defer the implementation.”

The Commission announced on May 16 that it was delaying the implementation of vegetable crop regulation in the North until January 1, 2026.

“This will give us time to consult with producers, producer organizations and other partners regarding the nature and extent of vegetable production in the North, and develop a commonsense approach to our involvement,” Solymosi said.

One of the issues the commission heard in the unsolicited feedback it received was that a lot of people haven’t even heard of the BCVMC, despite the fact that it’s been around since 1935.

Regional District directors echoed this concern, along with questions about the format the belated consultation will take.

“What form is your consultation going to take,” Board Chair and Area C Director Brad Sperling asked. “Are you going to come up and do presenations?”

Derek Sturko, Chair of the BCVMC said that the commission is a small organization, so consultation will likely be a combination of in-person sessions and webinars or Zoom calls.

“We’re developing a plan and an approach for consultation,” he said. “We’re speaking to local governments, regional governments and Farmers’ Market Associations before developing a plan to get that feedback.”

Sturko said the goal is to have the consultation done by May or June 2025, so they’ll “have time to figure out what to do in response.”

The British Columbia Vegetable Marketing Commission is responsible for the orderly marketing of vegetables. The regulated vegetable industry in BC is organized under the Natural Products Marketing (BC) Act and the British Columbia Vegetable Scheme. As the first instance regualtor, the BCVMC is responsible for administering the scheme, which prescribes the rules, procedures and application for vegetable marketing.

“We do this by the promotion, control and regulation of production, transportation, packing, storage and marketing of regulated vegetables grown in British Columbia,” said Solymosi.

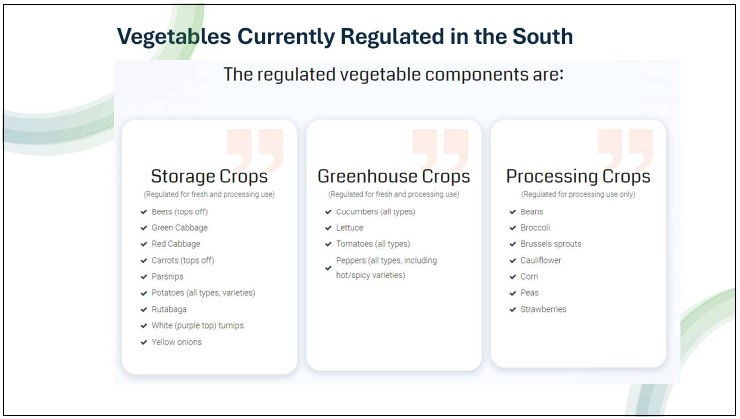

“All vegetables come under our authority, but only certain vegetables are currently regulated,” he said.

Storage and greenhouse crops, for both fresh and processing use fall under the regulations.

Storage crops include beets, green cabbage, red cabbage, carrots, parsnips, potatoes, rutabaga, white turnips and yellow onions. Greenhouse crops include cucumbers, lettuce, tomatoes and peppers.

Processing crops are regulated for processing only and include beans, broccoli, brussel sprouts, cauliflower, corn, peas and strawberries.

Solymosi said that all these crops became regulated when producers unanimously voted to do so. The commission’s decision was “applied after a fair and transparent process where growers determine if they want a specific vegetable regulated.”

The role of BCVMC is to provide industry stability by managing market growth and avoiding over or under supply of vegetables. Distinguishing between producers and marketers is key to effective resource management.

“Producers produce product; marketers market product,” he said.

“We want consistency in food safety and other production practices, so in the end it provides a level playing field. We want to ensure that there are options available for British Columbians and that there is food security.”

The BCVMC provides for industry stability through licensing for industry participants; a centralized marketing structure; a compliance and enforcement structure to ensure orderly marketing; and minimum pricing so marketers compete on quality and service.

Regulated marketing benefits producers by maximizing grower returns, managing market growth, efficiently managing resources and thus focussing on food safety and food security.

Solymosi said that regulated marketing enables organizations to either focus on growing or distributing vegetables.

Production thresholds for regulation were questioned by PRRD directors, who were concerned that the thresholds would have a negative impact on farmers’ markets.

“Farmers’ markets already have bylaws and regulation in place,” said Area B director Jordan Kealy. “As long as we adhere to the health authority, we’re legally selling product and matching food security based in our areas, and producers know those best.”

“How is it that the commission thinks it can do that better?”

Currently, a producer is defined as a person who operates a farm where one tonne or more of the regulated product was produced in the previous 12 months. A commercial producers is a producer that has grown a regulated product that has a gross value to the producer of $5,000 or more.

“This is where we need to reassess,” said Solymosi. “Where does our regulation get applied? Do you have sufficient regulations to accomplish the outcomes you want?”

Area E director Dan Rose thought it sounded like a quota system.

“If someone comes in to get licensed and you already feel there’s enough of that product, will they get turned down? It sounds like supply management to me,” Rose said.

“If you have a solid business plan in place and a market for that product, there’s no issue,” said Solymosi, adding that new entrant applications are usually only rejected for a lack of information on the application, such as an incomplete business plan.

Kealy agreed with Rose. “You’re applying supply management to private producers. You say you’re doing it for food security, you’re not. Trying to regulate all smaller producers is going to create havoc and you’re going to have a lot of people angry with you.”

Sturko said that “in principle, it’s not supply management.”

Sturko and Solymosi said that the BCVMC is determined to find out what works best for the north, in terms of pricing, regulated products, thresholds and representation on the commission.

“We’re starting fresh to make sure we do this right and do enter into the northern part of the province in a way that’s appropriate for everybody, not just us,” Sturko said.