Minimum nurse-to-patient ratios keep patients, communities safe

Imagine that you run a small community hospital. You have two nurses on duty, responsible for 20 patients. A patient comes into the emergency room, who, during treatment needs to be intubated. That patient then needs one-to-one care, leaving the second nurse responsible for the 20 other patients in the hospital.

You put the call out for additional help, but no one can come in.

What to do? Risk the wrath of the community by closing the ER? Or compromise the safety of the patients already in the hospital by redirecting one or the other of the two nurses to help the next person to come into the ER?

Because there’s no capacity to treat another patient, who might turn up with a broken wrist, for example, your ER must close, and the patient in need of emergency care has to go to the next nearest hospital.

This was a possible scenario outlined by BC Nurse’s Union Lobby Coordinator for the Northeast Region, Raelene Stevenson during her presentation to the Peace River Regional District board of directors at their regular meeting on March 20.

“It is not ideal,” Stevenson said of going on diversion.

“We don’t want that to happen, I don’t think anybody wants that to happen,” she said. “When you have things like stroke, time is brain. You need to have that person immediately sent to the next closest available place.”

“In addition to that, it is that nurse and those staff that will wear the tragedy if the person does not get the care, they need by going on diversion.”

The Ministry of Health has tried a variety of measures to address these workload issues without success, and now the BCNU is looking to mandatory nurse-to-patient ratios as a way to solve this chronic problem within British Columbia’s healthcare system.

In April 2023, the BCNU ratified their collective agreement, which included a $750 million commitment from the province to implement minimum nurse-to-patient ratios.

“Patients are safer, there is so much research out there that show that better nurse staffing decreases patient mortality,” Stevenson said.

“More nurses translates to better, safer care and implementing mandatory minimum nurse-patient ratios translates to better recruitment, retention and nurses on the floor.”

While this will be the first time ratios have been tried in Canada, Stevenson says that other jurisdictions such as California and Australia have implemented ratios with great success, leading to strong increases in nurse registrations, nurses who say they’re more likely to stay in their jobs and decreases in hospital vacancies.

“We’re the guinea pig.”

Smithers has already begun implementing the ratios, and Stevenson says that nurse satisfaction and patient care have gone up exponentially, while nurse sick time and patients returning to the ER to access healthcare has gone down.

Research has shown that when entire hospitals are properly staffed, not just ER’s, burnout is greatly reduced. Stevenson said that when nurses keep working extra shifts because they want to help, if they’re burned out, both patient and nurse safety is compromised.

“It’s not that we don’t want to show up and make sure that these ERs are not going on diversion,” she said. “But if it’s my family member on that bench later, I want that nurse to be safe. I want safe care.”

That, she said, is a big piece of why ratios are in such demand and need to continue going forward.

“We want the nurses to come and things to be safe, because we want our communities to be safe. We want our communities to thrive and be healthy.”

Stevenson said that making the ratios mandatory gives it teeth. When the public knows that there are minimum mandatory ratios and what they mean for the quality of healthcare, they and local governments can help make sure the challenges in their communities to recruiting nurses are addressed.

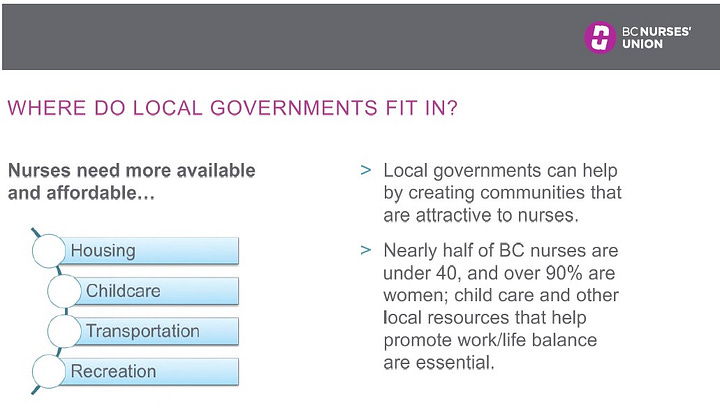

Local governments can help by creating communities that are attractive to nurses. For example, nearly half of BC’s nurses are under 40, and over 90 percent of them are women, so childcare, recreation, affordable housing and other elements that help promote a work/life balance are essential.

“Partner with us in educating the public, your constituents about healthcare challenges in our communities and what needs to be done to address them,” is something else local governments can do.

“We strongly believe that one of the most important factors in fixing the problems in healthcare is having a public that is educated on both the problems and the solutions,” she said.

While there is no magic bullet solution, 84 percent of over 15,000 BCNU members surveyed said that ratios were a “must have”.

“Money doesn’t drive this. What drives it is we want patients to have successful outcomes. We want families and communities to be safe.”

“I work in ICU. If I have three ventilated patients, I don’t care about $5 more an hour. That doesn’t make me three people.”